Saracatinib (AZD0530) began its journey as an ATP-competitive tyrosine kinase inhibitor aimed at mitigating the pathological signaling of the Src family kinases (SFKs) and Abl kinases. The rationale for oncology was strong: Src is pivotal in cell proliferation, invasion, and metastatic processes, while Bcr-Abl plays a role in leukemogenesis. However, the oncology trials were disappointing. Tumor shrinkage did not occur, progression-free survival mirrored the placebo, and AstraZeneca eventually discontinued its development as an anticancer asset.

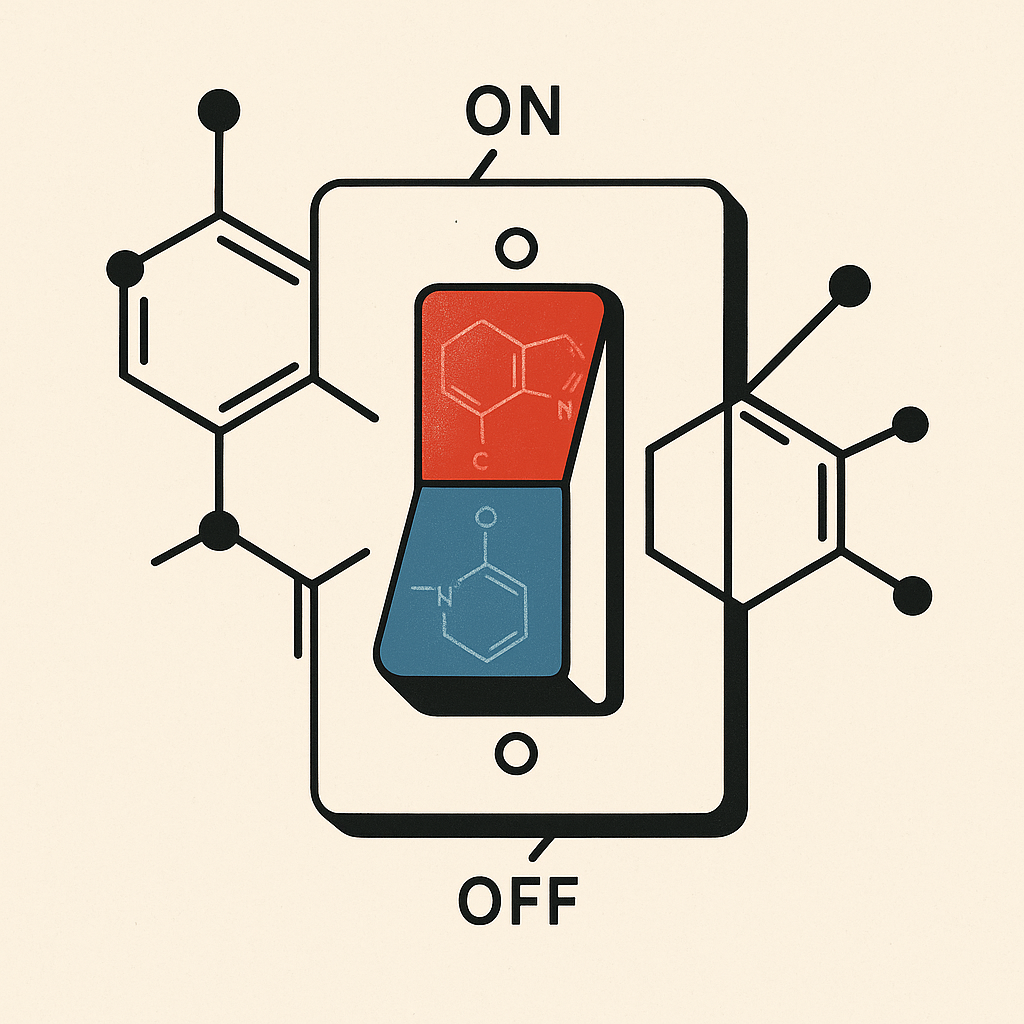

Yet, saracatinib's story did not end there. Like many kinase inhibitors, its mechanism is versatile enough to impact pathways beyond oncology—fibrosis, synaptic plasticity, even mast cell activation. This versatility, combined with tolerability, allowed it to be "re-found" in fields far from its original intent. In neurology, its ability to penetrate the CNS and selectively inhibit Fyn kinase—an SFK isoform associated with the post-synaptic density—made it a promising candidate for Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Mechanistic Lens: Why Fyn Matters

The connection between Fyn and AD lies in the toxic interaction between Aβ oligomers and NMDA receptor complexes. In the presence of soluble Aβ, Fyn becomes pathologically activated, leading to excitotoxic cascades, aberrant tau phosphorylation, and synaptic injury. In preclinical models, silencing or pharmacologically inhibiting Fyn restores synaptic transmission and improves memory performance. Saracatinib, with its oral bioavailability and brain penetration, achieves central Fyn inhibition in both animal models and humans.

At the molecular level, this is not merely blockade—it disrupts the feedback loop between extracellular amyloid toxicity and intracellular kinase-driven excitotoxicity. In theory, this should slow synaptic degeneration even with persistent amyloid burden.

Clinical Experience in Alzheimer's Disease

Phase 1b and 2a studies confirmed what preclinical researchers hoped: saracatinib penetrates the brain, engages its target, and is surprisingly well tolerated even in frail, elderly patients. Unfortunately, the 52-week randomized trial in mild AD (NCT02167256) found no statistically significant differences in metabolic decline on FDG-PET or in cognitive endpoints such as ADAS-Cog and MMSE.

There were intriguing hints—slower atrophy rates in hippocampal and entorhinal regions—but these did not rise above exploratory noise. Essentially, saracatinib demonstrated pharmacodynamic reality (Fyn inhibition in humans) but not clinical efficacy. For neurologists, the trial underscores a common theme in AD therapeutics: the target can be real, the mechanism plausible, yet the clinical window unforgiving.

Beyond Neurodegeneration: Fibrosis as a Case Study

Parallel to the AD work, pulmonary researchers discovered saracatinib's anti-fibrotic potential. Using computational drug-repurposing models, saracatinib was predicted—and then confirmed—to reverse pro-fibrotic gene signatures. In vitro, it suppressed fibroblast activation and collagen synthesis. In mouse models of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, it outperformed or equaled established drugs like pirfenidone and nintedanib. More compellingly, in human precision-cut lung slices from IPF patients, saracatinib reduced collagen deposition and gene markers of fibrosis.

The ongoing STOP-IPF trial is exploring this translational bridge. While preliminary, the rationale is straightforward: Src and Fyn are critical kinases not only in synaptic excitotoxicity but also in fibroblast signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. The same molecular language underlies two radically different pathologies—neurodegeneration and fibrosis—and saracatinib is one of the few drugs bridging both domains.

Safety and Pharmacology: A Quiet Strength

From a prescribing standpoint, saracatinib's most notable quality is not efficacy but tolerability. In oncology, at 125-175 mg daily, dose-limiting toxicities included anemia, fatigue, and diarrhea. In IPF and AD, with doses reduced to 50-125 mg, side effects were mostly limited to mild GI upset or rash. No cardiovascular red flags emerged, and crucially, CNS tolerability was clear: no worsening of cognition, mood, or sleep.

Pharmacokinetically, it is orally bioavailable, metabolized hepatically (CYP3A4), and achieves CNS levels above the inhibitory constant for Fyn. It is not renally cleared in a clinically significant way. The half-life allows for once-daily dosing. A notable pharmacodynamic effect is the inhibition of osteoclast activity, measurable as a reduction in bone resorption markers—clinically neutral for most patients but worth monitoring in long-term use.

Neurological Implications Moving Forward

So where does this leave us? For AD, saracatinib in its current form seems unlikely to progress. The failure was not catastrophic, but it was definitive enough to temper enthusiasm. Yet, the pharmacological lesson persists: Fyn remains a valid target. Future iterations may combine saracatinib-like Src inhibitors with anti-amyloid therapies, leveraging amyloid clearance while dampening the downstream kinase storm.

For fibrosis, including neurological fibrosis such as in chronic demyelinating conditions or post-stroke gliosis, the implications are promising. If saracatinib can influence the universal biology of fibroblast and glial scarring, it may one day join our toolkit not as a neurodegenerative drug but as an anti-scarring agent.

And for oncology, saracatinib serves as a reminder: drugs can fail in their intended field yet illuminate unexpected therapeutic pathways.

Closing Reflection

As neurologists, we often inherit compounds from oncology—kinase inhibitors, immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies. Saracatinib embodies this migration. It is a drug whose true narrative lies not in its first act but in its second and third. For now, its utility in our clinics remains investigational. But the fact that a single molecule can bridge cancer, fibrosis, and Alzheimer's highlights a deeper point: neurology is increasingly defined not by organ system boundaries but by molecular commonalities across diseases.